This is the second installment from the novel writing course through Curtis Brown  Creative in London, under the mentorship of author Nikita Lalwani and with fourteen other novel writing peers. As I said in my previous posting, the bulk of the work is evaluating 3,000 work segments of each other novels, but we also get little voluntary 500 word homework assignments we can submit for peer review as well. This week, in which we focused on endings, the assignment was to rewrite the ending of a favorite novel.

Creative in London, under the mentorship of author Nikita Lalwani and with fourteen other novel writing peers. As I said in my previous posting, the bulk of the work is evaluating 3,000 work segments of each other novels, but we also get little voluntary 500 word homework assignments we can submit for peer review as well. This week, in which we focused on endings, the assignment was to rewrite the ending of a favorite novel.

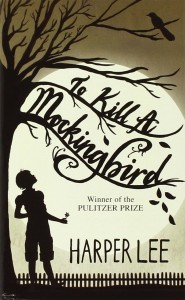

I am predicating an alternate To Kill a Mockingbird, told from the viewpoint of a black girl who was sent from Chicago with her brother to Maycomb, Alabama, to live with her Aunt Helen and Uncle Tom because the pollution in Chicago is bad for her asthma. While they are there, her Uncle Tom is charged with rape, put on trial, killed…(I didn’t feel I had a handle on Southern Black dialect from the 1930s.):

Miz Richardson wouldn’t let Mama take off work right away to come get Jem and me after what those men did to Uncle Tom, because Miss Susan was getting married. So while we waited, the ladies from the church came over with food for Aunt Helen and our cousins. They cleaned the house, swept the yard, even boiled the water for our baths on Saturday. They combed out our hair into pigtails so tight that I had to work my eyebrows loose. But I didn’t complain, like I would have for Mama or Aunt Helen.

Some colored men from out of town in suits came to talk to Aunt Helen with that white lawyer who defended Uncle Tom. He smiled at Jem and me all sad like and said he had children our age. He even had a boy named Jem. They want Aunt Helen to go to Washington, DC and tell her story to some important people so that white folks in the north will understand what’s happening in the south. But Aunt Helen can’t hardly even talk to her own family, so how’s she going to talk to white folks up north?

Half the people in the neighborhood came into the house when that Atticus lawyer and the men in suits came to see Aunt Helen, and someone must have spread the word, because then the pastor came and half the church. They told us we should shake the hand of that lawyer and that he was a great man.

“If that were true,” he said, “Tom would still be alive.”

Aunt Helen, she just look at him like, so some white man finally said something that make sense.

All of the people, the smiles at the white man, the sad looks at my aunt, they began squeezing the air out of my lungs. I grabbed Jem’s arm.

“I can’t breathe,” I said.

He got me out of the room, and out under the tulip tree; I began wheezing. He ran around the side of the house, brought some mint and crushed it against my nose.

“Hold that breath, and count to five” he said. “Now let it out,” and soon the world was more than just my breath again; I heard locusts and the hum of the sawmill up the road.

A truck drove by the house with two white men in the flatbed. One had a gun. We started to get to our feet to run for the house, but they just laugh and the one without the gun hold his arm up high in the air like his head in a noose and shout, “Next time we’re coming for you, niggers!”

Mama sent us down here from Chicago so we’d get some fresh air, but sometimes the air in a place, even if you can’t see it or smell it, holds more poison than all the smoke and soot put out by the South Works or the Illinois Central line.

You must be logged in to post a comment.